How to Make Dance in America

A manual for independent dance makers

Lily Kind

Copyright 2024 Lily Kind — Published with permission

Table of Contents

Introduction

Welcome!

You are reading a small manual that outlines the technical, creative, and logistical basics of making and producing dance in America today. This manual can help you if you have questions like:

- Where do I even start?

- What the hell is the difference between a DMX and an XLR cable? (See Part 4 “The Nitty Gritty” for the answer.)

- How do I figure out the power dynamics of being ‘in charge?’ OMG this is so time consuming; Is it worth it?

- How do I run the front of house? What is front of house?

This ‘Zine exists because:

Both a ‘non-dancer’ starting to make performance art and a seasoned professional working on a first attempt to self-produce without institutional support face similar challenges. Both creators might wonder, more broadly, about how to proceed independently, without a large budget or other traditional resources. This manual is focused on dance but could be helpful with all kinds of DIY performance production.

There are many reasons to dance. Dance doesn’t always begin with a desire to share dance performances. Many of us make dance as a way to reclaim our body from our daily grind or to get out from under social norms. For some of us, dance is a visceral response to music or sound. Others dance as part of their spiritual practice. Some dance to be part of a community, to fight against the individualist narratives that dominate our daily lives. Some dance for the glory of winning competitions, or to make money and pay the bills. Often, many motivations intertwine.

The overall thesis embedded in this manual is that how you make the dance is as much a part of the content of the dance as the dancing itself. This manual doesn’t outline a particular method of artistic process. However, the resources I offer here reflect my interest in how the artistic process and the production process overlap.

This manual is a tool of resistance against dominant ideas about dance in the United States specifically. I’m saying ‘America’ in my title, instead of the USA, because I think it sounds better. But of course the Americas include Canada and Central and South America and I don’t know as much about making dances there. I make US American dances, whether I want to or not. My nationality, while an incredible privilege most days, is an identity I experience from the outside in. This ‘zine is for anyone who, like me, wants to make dances differently than the dominant methods in the US, ie. with greater freedom and in community. In the Living with Capitalism section, there’s more about funding. In the USA, we have a particular arts funding conundrum, predicated on the lack of general social welfare programs for everyone.

Historical acknowledgement: In short, since European colonizers first occupied what is now called the North American continent, the development of colonial power always went in tandem with outlawing, forbidding, degrading, or appropriating dance practices. Everything from the great multitude of West African sacred and secular dances that enslaved people brought to this country, to the dances of the various tribes and nations thriving on Great Turtle Island, to the dances of European peasant immigrants, ranging from Irish jigs to the waltz, to jazz and swing dances, to various Hip Hop forms, all have been considered ‘dangerous’ or ‘immoral’ by those wielding political or religious power in the name of capitalism.

Who I am:

This manual has also been informed by more than a decade of producing my own work. It is the resource I wish I’d had when I started making dances during the economic recession in Baltimore in 2009 as the founding director of the Effervescent Collective. I first started writing down this knowledge to better share it with others as the Director of the Artists-in Residence Program at Urban Movement Arts (UMA) in Philadelphia. UMA was a pretty scrappy organization when we first got going, the brain child of my buddy Vince Johnson – who definitely knows how to make something out of nothing. Much love to all the artists who interacted with UMA’s residency program. Special thanks to Majestique, Sanchel Brown, Lauren Auyeung, and Lillian Ransijn, whose feedback has informed this text. Shout out also to Dr. Gale Jackson who encouraged and edited early drafts of this ‘zine.

I’ve been able to help folks new to self producing or DIY making, regardless of their dance background or training, gain more freedom in how they share their dancing with audiences. It may be helpful to know that I am a white, able-bodied person. These privileges give me blind spots; I have tried to write this manual in a way that makes it easy to take what you like and leave the rest.

Drawing!

I include technical drawings because I think they help and also ‘cause I like making them. For me, the act of drawing helps me see how the component parts of things fit together. Drawing taught me a way of seeing what’s really in front of me, rather than what I assume is there. I think this is a critical choreographic skill but I didn’t learn it from dance classrooms, I learned it from hours and hours of staring at bodies and objects and trying to recreate them on the page — a kind of visual listening. I include drawings knowing that times change, technology shifts, and what’s available at a local store, in a friend’s basement, or online may not look the same from one season to the next.

Part 1: What are we doing?

What does ‘making a dance’ mean?

When I say “making a dance", I am referring to two parallel processes:

1. An artistic process

We can zoom in on, for example, a specific sequence of movements that are meant to happen in a certain order within a very short period of time. A common unit choreographers often use is “8 counts.” We could call these tiny units micro-choreographies, but let’s just call them choreography. Choreography can also mean how many small units fit together within a specific space and across a longer period of time. We can call that composition. We compose when we are making a drawing, a piece of music, or even a meal, it’s how the parts fit together.

2. A production process

I think of this as macro-choreography: zoomed-out on a bigger scale. How long is the process of creation? Do you post the dance to the internet and wait for it to go viral? What is the training or preparation time for the dancers? How does the audience arrive at the dance? Do they participate or not? Does doing the dance change with age?

The idea that the material of the dance can be understood apart from the viewed performance of the dance is a rather strange notion. It erases the power relationships and belief systems we are looking at when we watch dance. The macro-choreography is always there, but sometimes we miss it.

Dance Mapping: Micro & Macro Choreography

Very often, certain norms are maintained as truths by those in power. They become invisible macro-choreography. There’s a helpful phrase that sums up this dynamic: cultural hegemony. This happens a lot in the dance context. A version of ‘normal’ is dear to those who need a version of ‘normal’ to exist because without it they would lose their power. It is the status quo masquerading as the truth. Sometimes the status quo is serving as our macro-choreography, without our awareness.

There are many, many ways of making dances that have been around, continuing to evolve, since way before the United States as we know it today became a country. The range of classical dances, folk dances, traditional dances — across the globe and spanning human history — offers many possible versions of how responsibility for making dance and making dance happen can be distributed. Distinctions between folk dance, traditional dance, and classical dance are hard to maintain. Such boundaries often serve the interests of the person or group making the distinctions. [1]

We could approach choreography very literally, as ‘dance-mapping’. The Greek root word is khoreios, or dance; and graph means map or chart. Most micro-choreography doesn’t need a map; instead, we need our muscles to know it in an instant. Some dancers make storyboards, like a filmmaker, if they’re composing long dances. This manual doesn’t go into composing dances, but in summary I would remind you you’re working with: space (depth of field and width, negative space, light), time, people, and gravity.

Getting Started

I find it useful to start with whatever is the most pleasurable. What is joyful to me about an initial impulse I have?

I’m a person who tends to see a dance ahead of time, not the specific choreography, but the feel, the environment, the overall aesthetic.

Maybe a specific place or location helps you clarify what you’re making, gets your juices flowing.

Maybe you find a certain soundtrack really generative, even though you know it won’t be music in the final show. No worries. Let it be generative for you. You can always edit later.

There’s no wrong or right way to make a dance. My first rehearsals are usually just messing around with friends, finding the right dancers/collaborators.

Sometimes I collect a lot of ingredients and then cut and collage. Sometimes I make a dance top to bottom, from the opening gestures to the final bow. You’re gunna have to find what works for you. Sometimes I have to save an impulse for a while, it’s just not the right time for a certain idea.

Once you’ve got some momentum, some material, how can you give yourself space to experiment?

Part 2: Time

DON’T SKIP THIS PART

I could go on about theories of ‘time’ in dance: Dance as the art of time, etc. But let’s be practical here. You can do amazing creative work but if you haven’t organized your time well, if you don’t plan, it’s gunna be a shit show. And you will end up pissing people off.

When I’m working towards a performance, I map my time backwards. Meaning, I count how many days, weeks, and rehearsal hours, I have between the show and now. I create a way to visualize it (example ↗). For example: Okay, so I want to have tech week the week before my show. That means, I need to have tested out all my tech the week before that. What do I need to test out my tech? Okay I’ll need to start gathering/borrowing materials the week before that. Set deadlines!

When I can get a friend to be my project manager, helping keep track of all the timelines, I gain so much extra space in my mind. If you have a friend who likes organizing or spreadsheets or accountability structures, ask them to help you!

Kinds of Timelines:

1. Creation & Rehearsal Timeline:

Work backwards from last show and “strike” (aka when you clean up from the last show) to today. Divide it however works for you.

I usually think in weeks.

Okay I want to do the show in mid August?

...It’s May now, I have twelve weeks from May 1 to August 1.

So, I’ll use the first six weeks to rehearse, take a week off, do two intense production weeks, take a week off, and then it’s show time.

2. Getting-Help Timeline:

YOU WILL NEED HELP. Expect to ask people for help or to donate services/skills to produce a show.

- How much heads up time will they need to help you? What deadlines work for us both? Do we need a check-in scheduled in there too?

- When can I see a draft or try out a mockup?

- How much time will they need to make changes after that?

- How long will it take for them to make the thing I’ve asked for: the longer the task will take, the sooner I need to ask the person!

3. The dancers’ time:

Frequency of rehearsals? (One weekly? everyday? once a month?)

Duration of rehearsals? (One hour, three hours, a full day?)

Dancer’s travel time, warm up time, snack time, and social time!

What does Production include?

Set,

Lights,

Sound,

Costumes (including hair & makeup),

Front of House (aka what audience sees),

Back of House (aka backstage)

For each of these categories, you need time to brainstorm a design, make a test design, test-out the design, edit the design, install the design, and after the show, de-install design and return the materials.

THESE ALL TAKE LONGER THAN YOU THINK.

I have learned to love spreadsheets.

Marketing

Time to create graphics and copy/captions for social media, printed flyers or postcards, write email newsletters, text friends, seek press coverage (tv, radio, film, podcasts, blogs) to promote the show and review the show.

Fundraising

Creating a fundraising campaign is about writing a compelling story of why people should support you. The longer you have to raise money, the more time you have to tell the story and spread the word.

Documentation

Start now! Find a photographer, videographer, and/or any other kind of documentarian. Hire, ask, or beg them to archive the performances (and maybe the process too!). Determine what time they will show up to your rehearsals or performances. Consider their travel time (and expenses). Consider the timeline of their getting files/prints/ links to you.

Timeline Examples

I offer you:

- Task List Example ↗ — A simplified version of a production checklist we used in the 2021 iteration of show Wolfthicket which we produced in the carpeted (yes carpeted) community center at the Lutheran Church. My pal Emily P, the volunteer production manager for that, is also to thank here. When you’re a tiny production team, a couple of people doing everything, this kind of tasklist can be helpful.

- Week by Week Example ↗ — A simplified week-by-week production plan to get you started. If you have a bigger team, this may help plan and track who is doing what when.

- Dancer Schedule Example ↗ — When I first started producing my own work (because no one else would!) I wasn’t in a position to pay dancers’ for their time. It’s generally hard to pay dancers a fair rate for their labor. This is tangled-up how in capitalism works in general. I’m not going to try to solve it here, but suffice to say I go out of my way to work around my dancers’ schedules. If, like me, you have to work around the schedules of friends who have multiple jobs outside of dance, here’s a way to stay organized.

Part 3: Space

"SPACE is the place!"

Where do you envision your dance? (in your imagination)

Where are you making your dance? (in your real life)

You might have a vision of making a dance in a library, but the only place available is a squash court.

First, keep talking to the staff of the library. Ask them (kindly) over and over again. Ask another librarian. Ask what might make it possible for the library to say yes. Maybe the folks who run the library are worried about noise, but actually that’s fine because you want the dance to be totally silent. Their concerns might give you more ideas like having the audience wear headphones or the dancers wear really soft squishy socks or slippers.

Try to meet people in person and have walking conversations. Walk through all the nooks and crannies and armpits and elbows of a space. Oftentimes, there’s some unused corner no one imagines you would want to use, but actually, that corner is PERFECT for you; not to mention, you’d have rehearsal privacy and they don’t even want to charge you for using the space. That would be nice, right? It doesn’t always work out that way, but it could happen.

People love proof of concept. Take a picture of yourself in that corner, improvise there for a few seconds (if that’s within your practice) so you can allow the people in charge of the space see how it could work. Show them it’s possible.

And then sometimes, it’s important to accept when working in a certain space is not in everyone’s best interest.

Sometimes the boundaries or needs of a space aren’t as they appear. Let’s go back to the library: Sh! It’s a quiet study place. But no: Maybe there’s also a joyful (and loud!) community story-telling hour event once a month. The same goes for a friend’s kitchen, the local pub, or a school’s multi-purpose space – notice your assumptions, ask about theirs, and get clear about what a space and its stewards need to thrive. It will make for a more nourishing process, happier dancers, and often better long term partners.

We may feel a space is ‘neutral’ when in fact, it never is. There’s no such thing! I think there’s is a kind of white, American, consumer modality that conditions us to ignore spaces we inhabit.

If the only place you have to make your dance is a boxing ring, your dance doesn’t have to be ABOUT boxing but it can still acknowledge a relationship to the boxing-use of that space. Otherwise, you’re asking your audience to IGNORE something obvious.

Getting to know a space

How does the space feel?

Sometimes there are very tangible reasons a space feels a certain way.

What’s its history?

How is it arranged?

Where does the light enter and at what time of day?

Is there background noise? A mechanical din? Perfectly silent? What materials are walls and floor and furniture made of?

✴ A space like an airport or a mall might make us feel like it could be any time of day, that buying stuff will make our life better, and that new things are better than what we already have. That’s because malls rarely have windows at eye level. So, all the lighting is fabricated. Things are made of plastic or marble; not a lot of wood or iron that shows the passing of time. Don’t get me wrong: this ype of environment might be PERFECT for your dance.

✴ Alternatively, if you are trying to make a dance about shopping in the USA, but the space you have available is a beautiful old barn, how can you make that barn FEEL like a mall? It doesn’t have to look like one, but it has to FEEL like one. We FEEL in lots of different ways, not just with our eyeballs and sense of light and color, but also with our sense of smell and taste (which triggers memory!), and our sense of touch. Bring in fluorescent lights, play low-key muzak from an invisible speaker, install (fake) security cameras.

Who Uses This Space?

Is there a community already using the space where your dance will take place?

If so, what do they use the space for? If there is a community, you are in a relationship with those people. Ignoring them is one form the relationships can take, but maybe you can do better.

Is the dance you’re making specific to this place and this place only? Or, are you building it to travel?

Do you rehearse in Space X and Perform in Space Y? What are some assumptions you have made about what you need?

Common Assumptions: often wrong

- I need Marley (a very expensive kind of floor covering used in traditional dance settings.)

- We must dance barefoot/in socks/in shoes.

- We must be seen at all times by the audience; or, we will need entrances and exits.

- We should face the front the whole time.

- The audience will arrive and be seated immediately OR the audience will arrive and do an activity/do nothing in a lobby-like space before we let them into the performance space.

Temperature:

Too cold? Too hot? Is there AC? Heat? Will the daylight affect my lighting scheme? Ventilation? How does the season affect the dance? If you turn on the AC/heat/fans are they super loud? Will you use a lot of energy?

Electricity:

Does it exist here? Do I need it or music or lights or something else? Where are the outlets and how do the circuits break down (more on that in the HARDWARE section).

Vibes

Is this dance part of other festivities? Will there be food or drinks? Is the audience arriving hungry/ tired/tipsy/thirsty? Who feels they have power over this space? Does someone own it? Are certain activities prohibited? What else is going on around the dance space? Are there other sounds, groups of people that will become part of my dance, invited or not? Band practice downstairs or a sporting event down the street?

Safety & Access:

- Are there rules about fire safety: exits and entrances and numbers of people allowed?

- Is the space accessible to someone in a wheelchair or on crutches? With limited vision?

- Think about not just entrances but mobility: does the audience roam? Is there spoken or printed text?

- Examples: My group Effervescent Collective once made a dance about smell. We performed it at 2640 Space in Baltimore, in the round, with a live band. A blind audience member followed up with me to share that he had an awesome time: touching the herbs given to each audience member, the smells of Old Spice being smeared on the floor or of lemon zest filling the cavernous room. Feeling the live band reverberating, and the heat and wind of dancers.

- Conversely, I made a dance once with a recorded monologue that played while I puttered upstage, far from the audience, changing my socks and snacking. Someone who could hear the tone of the monologue but not see the inconsequential details of my movements would miss the contrast I was after.

- Is the performance scheduled for a holiday when trains and traffic isn’t the usual? Will a nearby sports event take up all the street parking? Is there CPR training happening in another part of the building – and someone who thinks they’re locked out of this work-obligated CPR certification will start pounding on the windows and cursing? Do I sound paranoid? Well, I’ve seen it all.

- Bathrooms: Labeled to welcome all genders? Stocked with adequate toilet paper and a small trash can? Soap and towels? Signs to find them easily?

- Theft: How to prevent loss or damage of equipment, gear, or audience possessions? How to protect and take care of things we need to make the dance work?

- Liability Insurance: Some venues will require insurance for the duration of your performance. That’s reasonable. You can buy liability insurance for one night, a couple weeks, or annually. You can buy it to cover a lot of stuff or a little. Expect to spend at least $100. You can also require everyone entering the space sign a waiver. I’m not a lawyer! This is not legal advice! Talk to the venue. They may have helpful advice to figure it out, because they want you to be insured.

Part 4: The Nitty Gritty

Lights & Stuff

Many people have helped their friends’ band load gear, Not enough people have helped their friends iron costumes, organize the backstage, or hang the lights. Does this contribute to many people’s sense that dance is somehow alienating, or ‘not for them’?

Capitalism rewards individualism and de-values service but do not get tricked! — there are folks out there whose special skill is helping someone else realize their vision. Notice who believes in you (YOU, not just your project) what they’re good at, and bring them into the process.

The Hardware Store

Nowadays, giant chain hardware stores like Home Depot are within thirty minutes of most urban and suburban centers. This is handy consumer convenience when you need a thing at 9 pm the day before the show. Being a humongous corporation, maybe they sell stuff at a cheaper price point, but it rarely accounts for external environmental and social costs. If you really need an extension cord at 2 am, try the nearest 24-hour drugstore or pharmacy (Walgreens, CVS, Target).

I prefer independently-owned hardware stores and appreciate their function in a neighborhood. Walking through the aisles stacked with shapes, parts and pieces gets me going. The local spot may have less in-stock, but they’re ready to order stuff if needed. When I find an employee who is interested in my oddball construction projects, it can be a real show-saver. This kind of relationship may take some time to develop.

I have a habit of inviting anyone working a service job (like at the hardware store) to come to my shows, often for free or a discounted price, without worrying whether they will actually attend, or not. Strangers can surprise us with their strangeness.

Building & Attaching Stuff

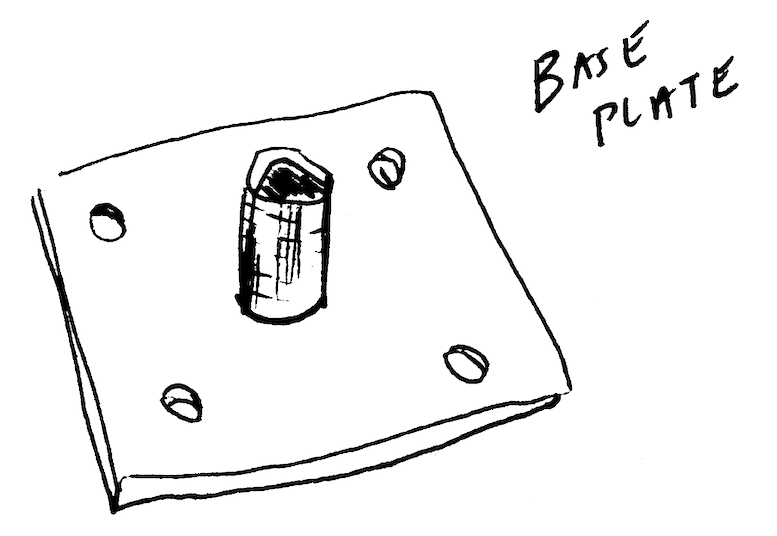

Base Plate

A heavy iron square with a fitting for a pole or pipe of standard dimensions. The heavy base alone makes for a handy base for a boom. (A boom is the vertical structure that you hang lights on.) If you run into it, “Boom,” you’ll get a big bruise. Check the gardening or scaffolding sections of the hardware store.

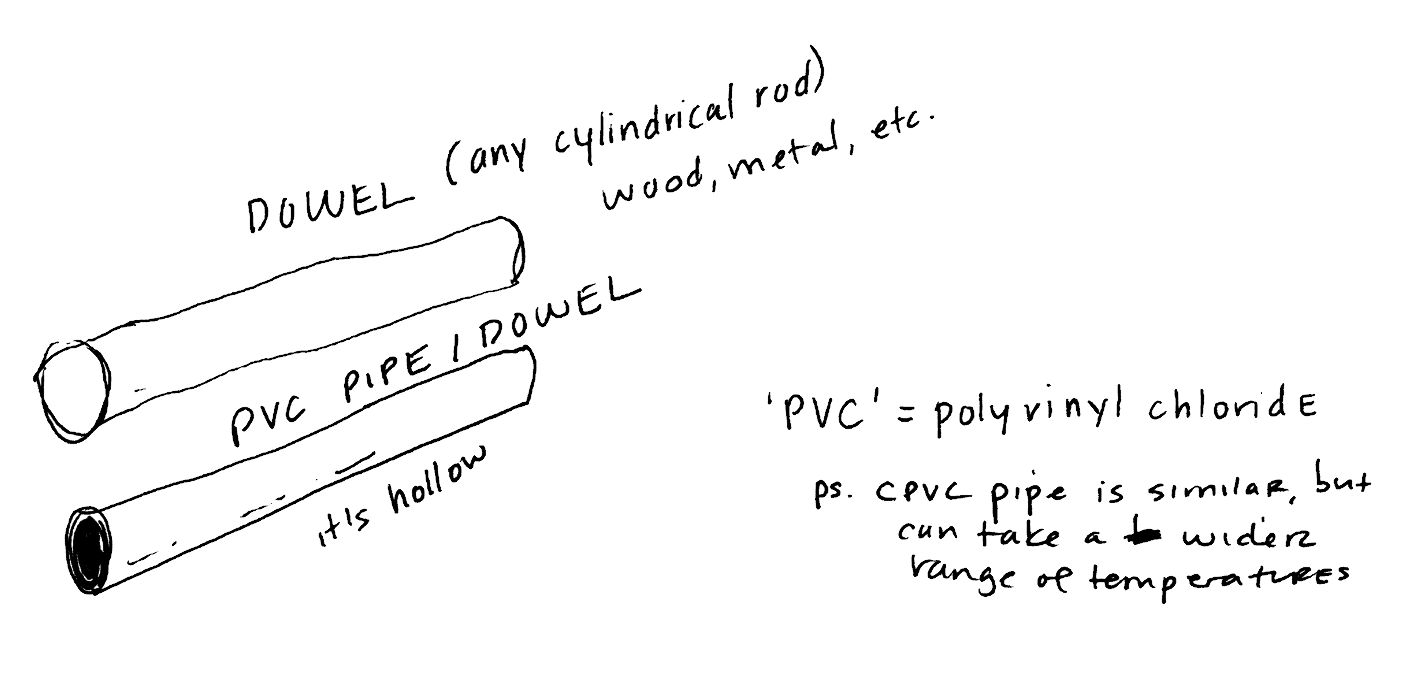

Dowels and PVC

Wooden dowels and PVC pipes come in multiple standard widths. Most places that sell them (like Home Depot) will cut them for you to any length at no extra cost. Either material can be spray painted to fit in or stand out. More expensive but super sturdy would be an iron pipe. Something to think about in choosing your material is its weight. Do performers move them within the show? Do you have to carry them upstairs to a storage closet after every performance?

Zip Ties

Plastic ties that make a zipping sound when you tighten them. This is a great safety precaution for anything that’s hung or attached, to ensure that nothing drops. A big box of them is not expensive. Unfortunately, most aren’t recyclable.

Gear Tie or Rubber Twist

A reusable alternative to Zip Ties, and often much sturdier. Like a humongous twisty tie, they have a metal center inside a plastic jacket. Most are waterproof. Choose wisely when putting zip ties on any material near heat or light. These are also great for organizing cables and cords.

C Clamp

A pretty sturdy way to secure one thing to another, if you can get the puzzle pieces and gravity on the same side. They come in all sizes.

Gaffe Tape or Gaffer’s Tape

In movies, the Gaffer is the head electrician on a movie set. A Gaff is a big hook you use to hang things (or catch things, if you’re a sailor/fisherman). Gaffe tape is expensive, but it’s very useful. It is better than duct tape because it rips easily, has a texture like canvas, sticks VERY well, and doesn’t leave as much of a sticky residue. You can put it on floors and walls without damaging anything. That said, even with gaffe tape, a super splintery wood floor will still splinter when you pull up the tape. The most common gaffe tape colors are black and white, but you can order other colors. I keep black and white around and use it for all kinds of things.

Steam Mop

A handy investment. An environmentally friendly way to clean floors. It is especially good for hardwood floors. The steam is so hot it disinfects.

Lights

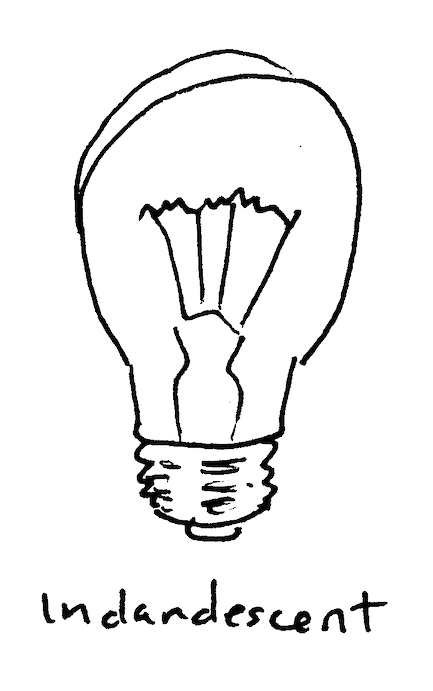

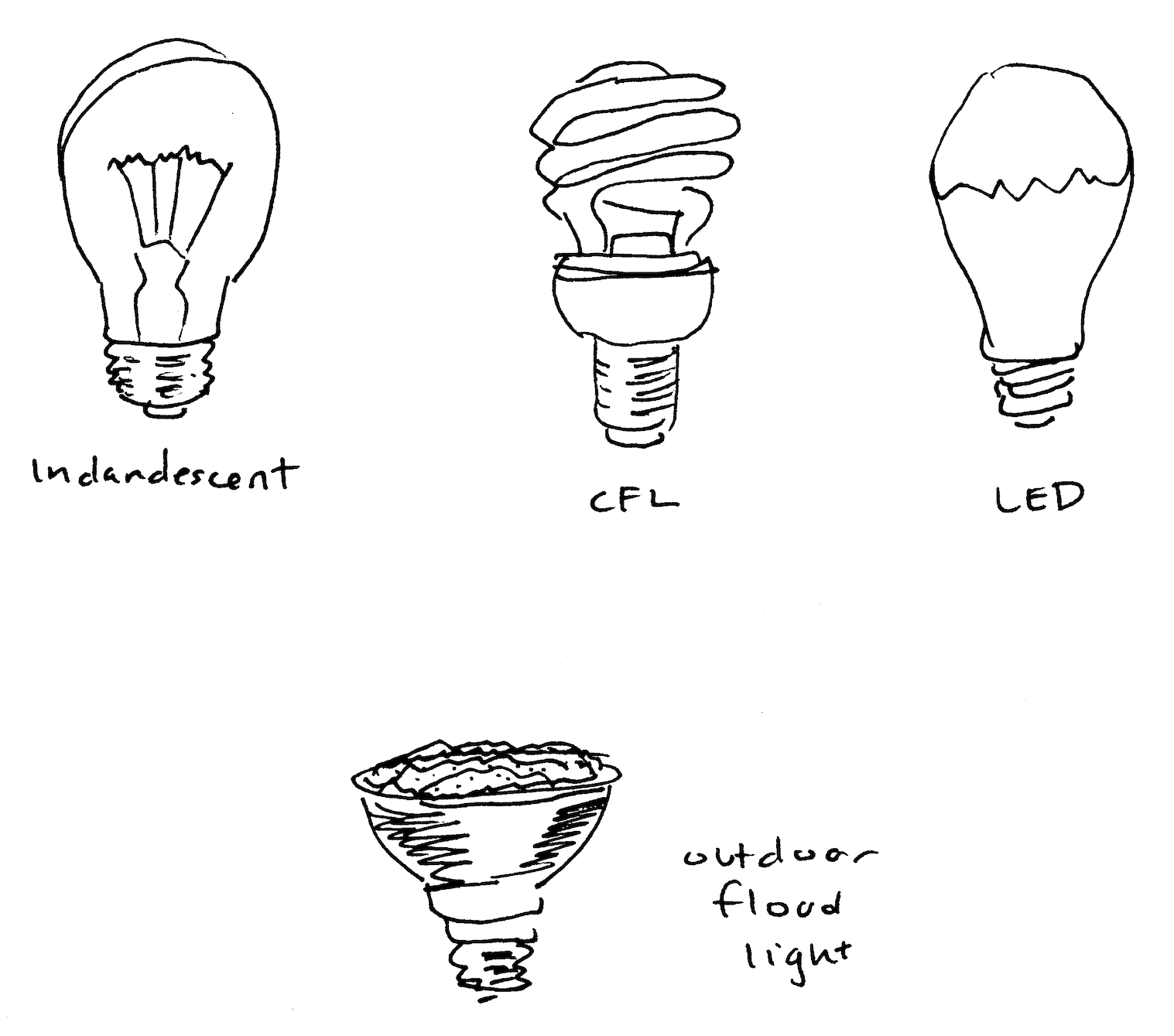

Light Bulbs

Watts measure the amount of energy a light bulb uses. The lower the wattage, the lower the electric bill.

Lumens measure brightness. Standard 100-watt bulbs produce about 1600 lumens.

The Lowes Lightbulb Buying Guide puts is succinctly:

Watts = energy use

Lumens = brightness

LED and CFL bulbs vs Incandescent “Standard” bulbs: CFLs and LEDs have a lower wattage than incandescent bulbs, but emits the same light output, or Lumens. I would argue that the light quality produced by the two types of bulbs is visibly different. CFL’s are often recyclable at big box stores like Home Depot and Lowes. Some general insights: LED’s tend to dim better and can handle cold temperatures. Warm White or Soft White is more like an incandescent light bulb, a slightly amber tone. Daylight is going to have more of a blue silvery fluorescent feel.

Clips/Clamps and Cones

I LOVE clip lights. The Cone is the silver metal part. Put the bulb into the cone, then screw the cone and bulb into the clip. Make sure your clip fixtures can handle the wattage of your lightbulbs. Clip lights are a cheap, fast, easy to pack up, way to put together lighting. You can buy colored bulbs or find/buy/borrow gels, which are a thin piece of heat resistant colored plastic you can tape over the cone.

Twinkle Lights (aka Christmas Lights)

These are fire resistant little lights, so you can put them BEHIND fabric or in a vessel, or wrap them around something without creating a fire hazard. They also make battery-powered packs which are handy when you don’t have electricity or you want a portable light.

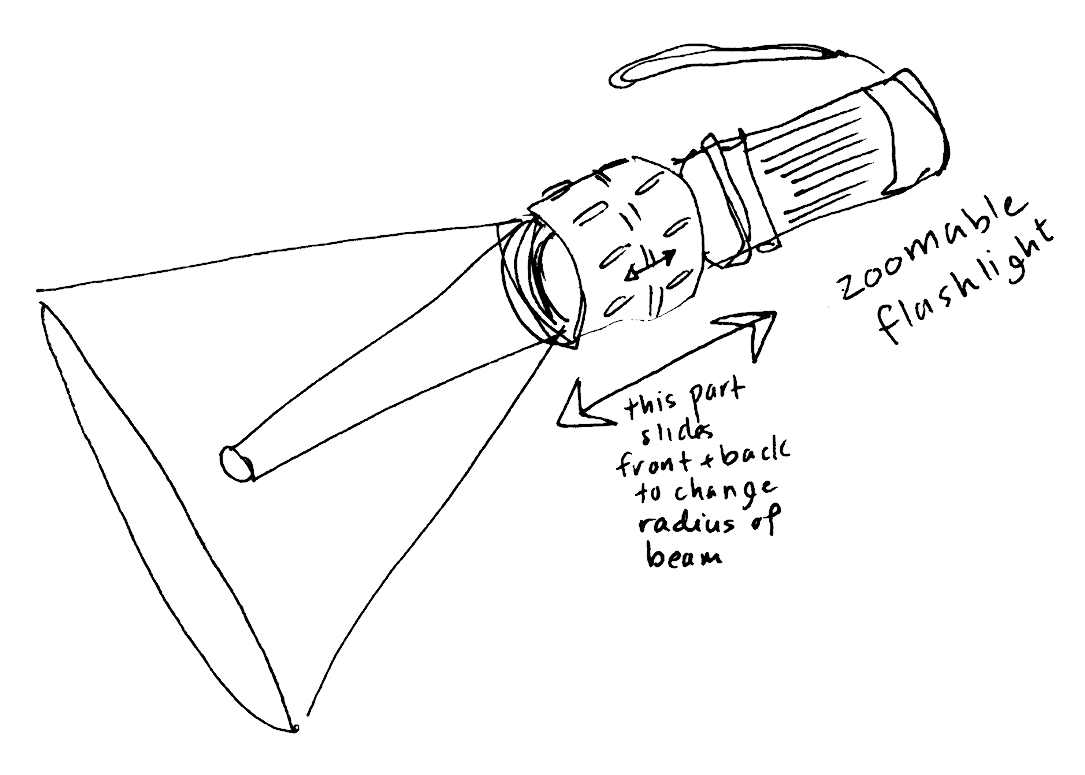

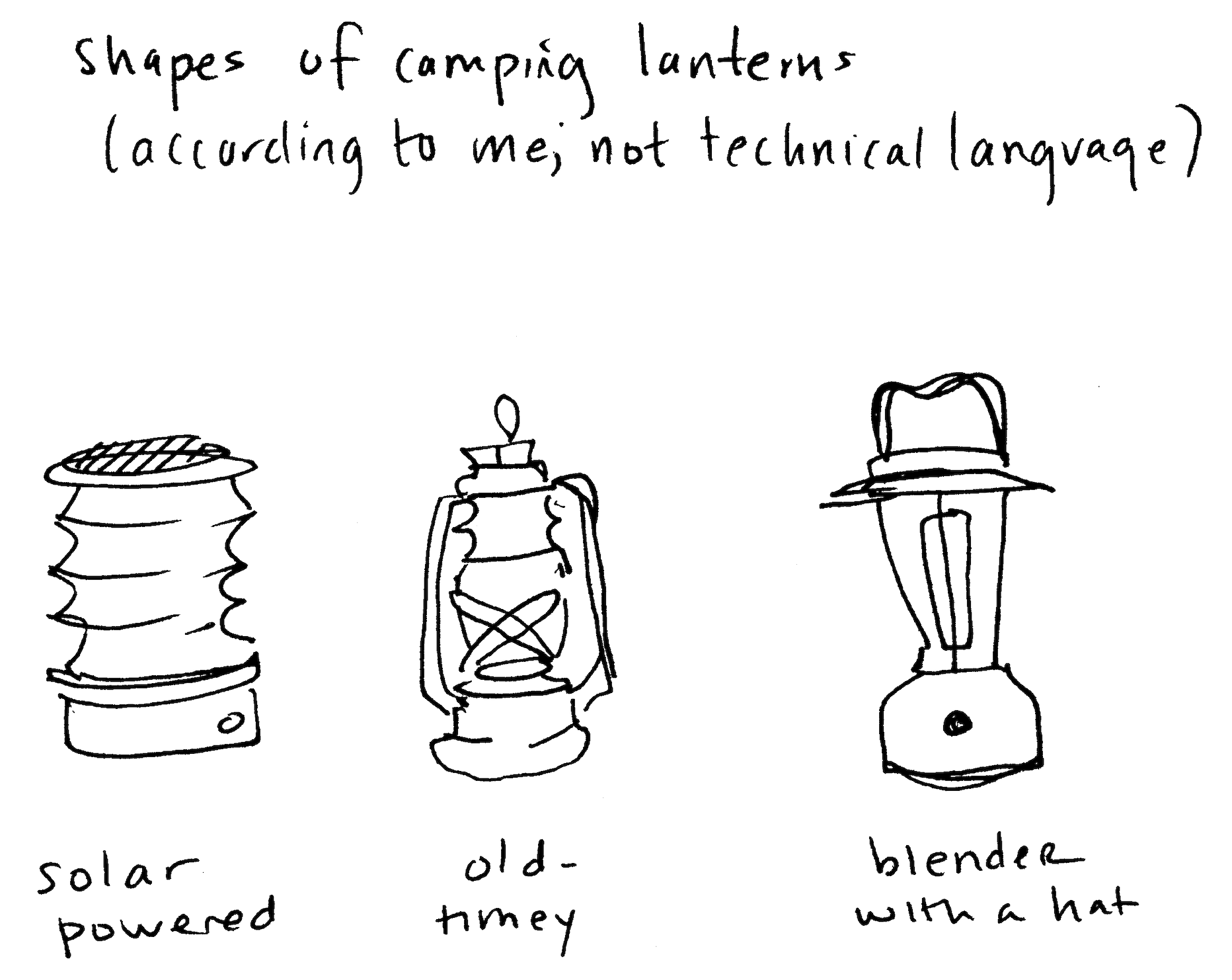

Flashlights & Headlamps & Camping Lanterns

You might have to find an ‘outdoor’ store like REI or EMS for these. Some headlamps and flashlights have different options you can cycle through, like flashing or red. Be really clear about the cycle. Say you want a serious moment with a red spot light, and you’re using your flashlight to get that effect, but when you turn it on, it starts flashing white. That’s not ideal. KEEP EXTRA BATTERIES AROUND. (Recycle your old ones.)

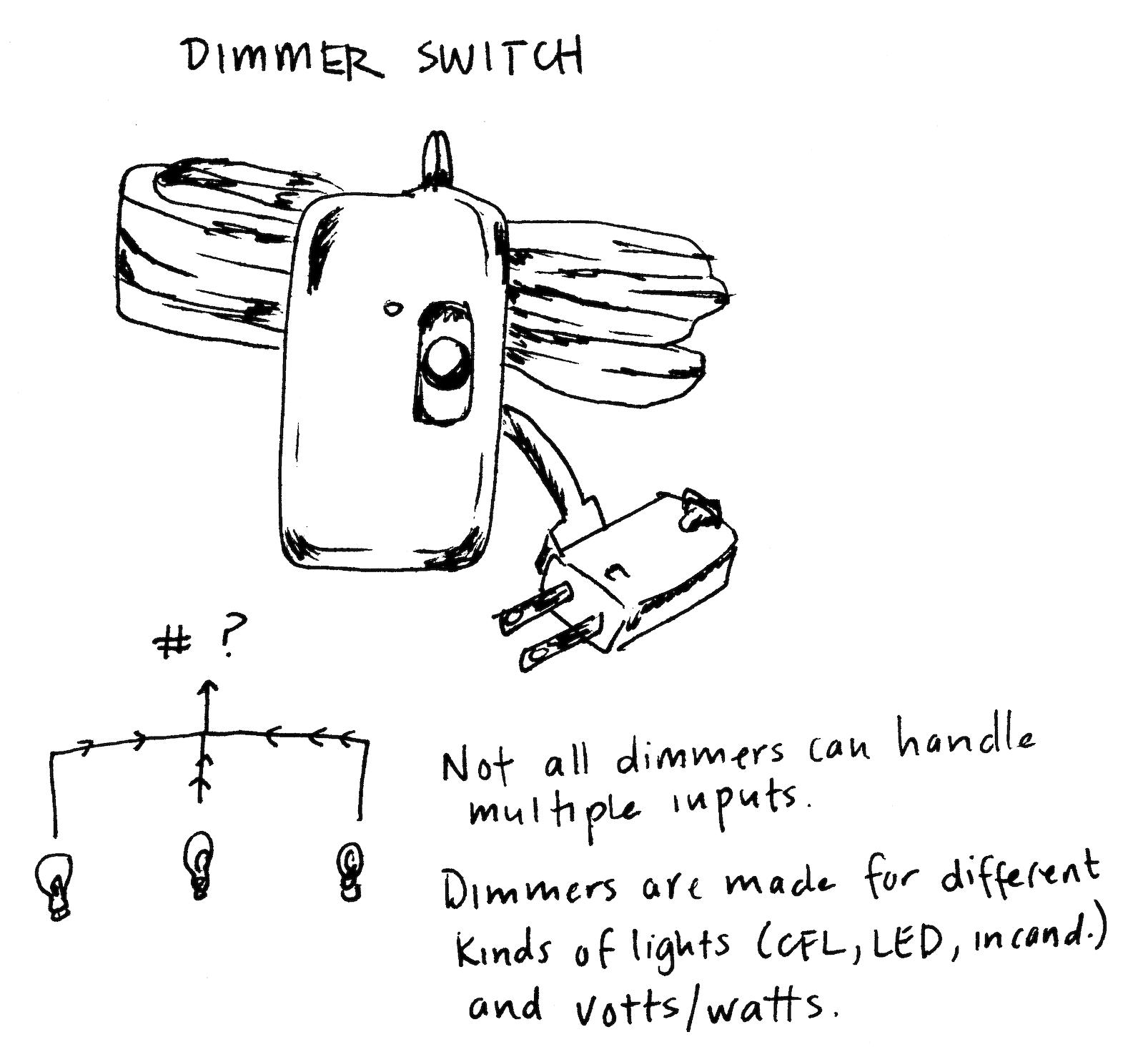

Light dimmer

The simplest version of this is a little slider switch you can attach to any outlet, to ramp up or down turning on and off a light.

Light board

An interface that allows a user to physically control various lighting fixtures at once. Many can be ‘programmed’ meaning the basic computer inside can memorize different Q’s.

QLab

A FREE computer software you can use to run sound and light cues from a laptop or computer. Product placement! It can do simple things and very complex things. In QLab it’s easy be able to edit que points for audio tracks on the fly. Its interface is very visual and they have lots of helpful tutorials online. Also it is owned by Figure 53, a small company with good ethics from my adopted hometown of Baltimore, MD. There is also a program called Show Cue Systems (SCS) for PCs that you can use on Chrome Book if you don’t need too many music files. It’s a little clunkier but still works.

PARs

There’s a whole world of professional stage lighting out there. One handy thing I started using recently are inexpensive PAR fixtures. I don’t know if these things have gotten less expensive in the past ten years, or I just got better at finding cheap ones. If you want to really get into it, there’s a lot of videos online. The diagram explains more. There are two additional categories of light fixtures, Fresnel & Ellipsoidal (also called Lekos). I don’t fully understand them.

Example lighting looks:

Outer space / inorganic / ‘un-natural’: LED lights, white/blue/fluorescent/glowing, un-seen fixtures. ie. Christmas lights in an opaque white vase. Fluorescent light stashed in a closet with the door cracked open. Aluminum Foil!

Vaudeville, cabaret, intimate spectacular: footlights, lights along the front of the stage pointing up at the performers. This creates a divide between stage and audience that can be manipulated. It also casts shadows onto the upstage wall.

Warm/organic: household lamps, yellows, oranges, sidelights so faces are clearly visible, visible lanterns, Edison bulbs, fake candles (or real ones if you dare! Take precautions: have them set in sand or floating in water, and know where your fire extinguisher is.)

Electricity & Cables

Extension Cords & Surge Protectors

You can buy surge protectors with individual switches. With these, you can make a basic light board. Plug different looks into different surge protectors, and then simply switch them on and off to turn on/off a look. Add a dimmer to two surge protectors that contain two different looks and you can cross fade.

Safety!

Basically, the more power something uses, the bigger the wires inside the cord are. The best way to start an accidental electrical fire is to plug something heavy duty into a skinny baby capacity cord. Or, use a messed up old cord that should be retired.

Use gear ties or zip ties to keep excess cabling tidy and so nobody trips. Shop around to find extension cords in fun, bright colors! Long, grounded, extension cords can be expensive; leave the tags on and return them good-as-new ;)

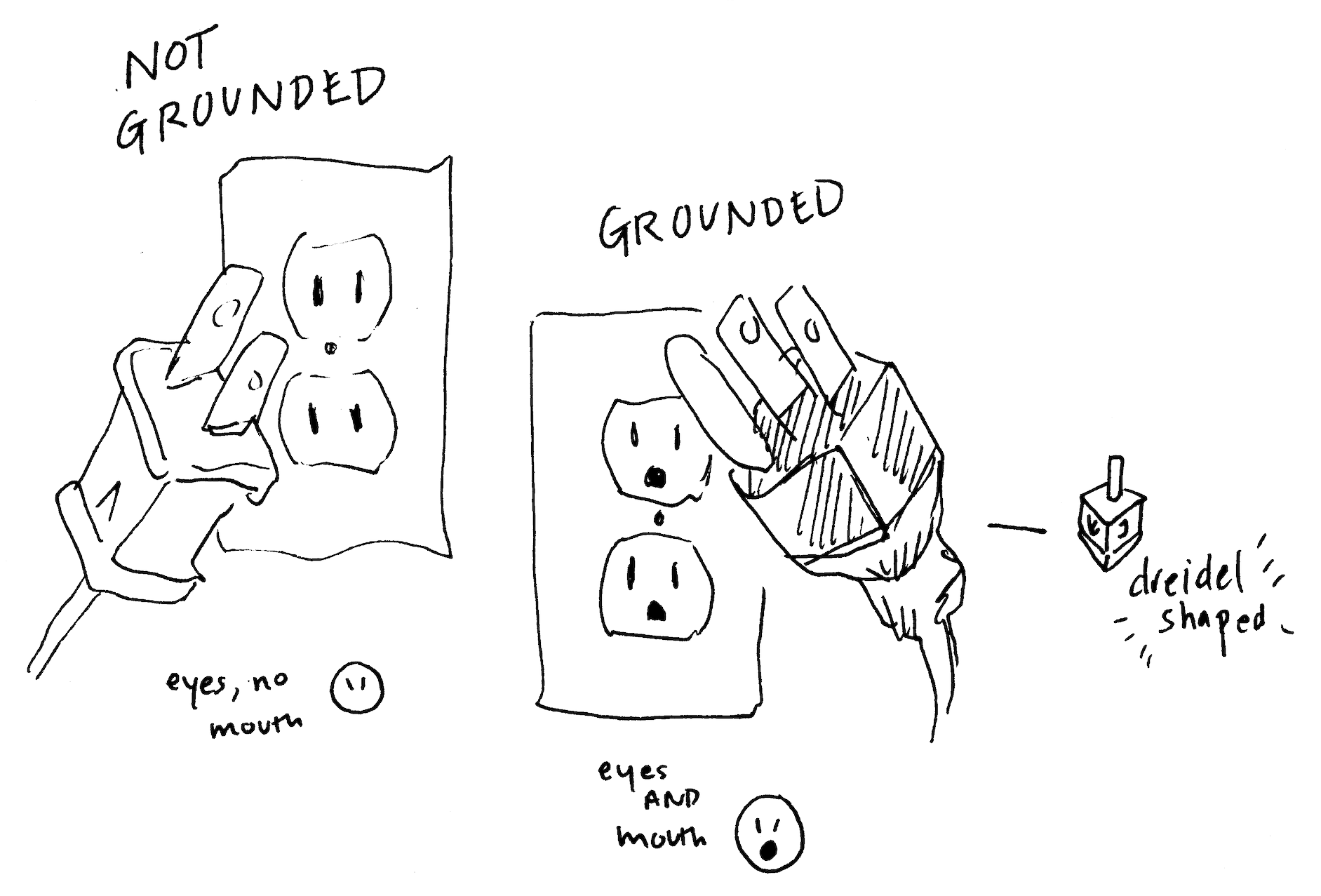

Grounded vs. Not Grounded

The third prong on a grounded cord reduces the risk of shock or fires. I’m simplifying here. I’m no electrician. Grounding means there’s a back up pathway for electrical current to travel along if for some reason it can’t go the way it’s supposed to. For laptops and electronics that don’t use a ton of power, go ahead and use a cheater plug (aka skeleton face) in a not grounded outlet. For lights and big speakers, or anything that generates hot or cold, probably don’t.

Circuits: Locate the circuit breaker panel in your venue. See if there is a description of how different lines are grouped into circuits. If you plug a hair dryer into the same outlet as a space heater, the circuit is likely to overload and turn off. This is a safety feature that keeps you from starting an electrical fire. Things that generate heat (or cold, like a refrigerator) usually take up lots of energy. So, consider carefully how you group your watt usage. If you borrow a friend’s fancy theater light fixture, don’t plug it into the same outlet as the mini fridge.

More Cables

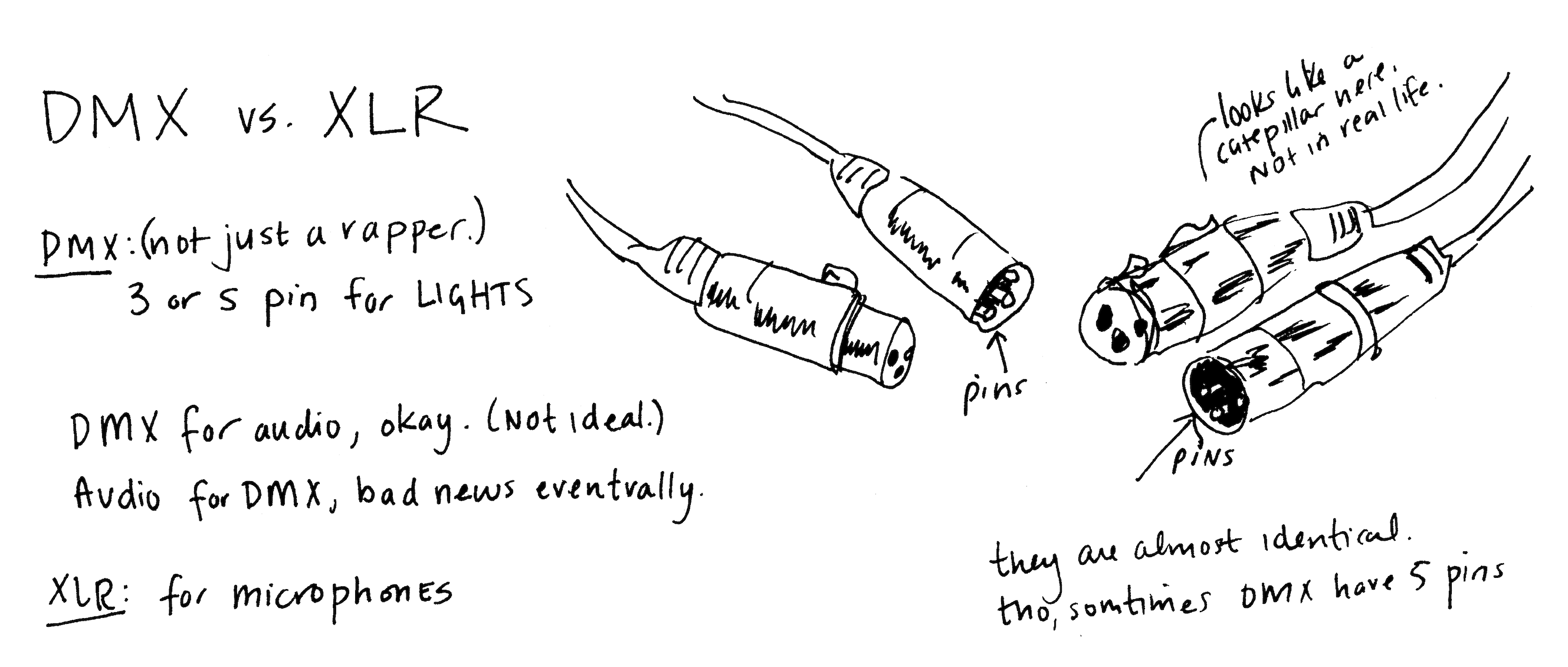

XLR

This is the kind of cable used to connect a microphone to a mixer, or a mixer to a speaker. I think of them as sound cables.

DMX

This is the kind of cable used to connect lighting fixtures to each other or to a lighting board. They have 3 ‘pins’ or 5 ‘pins.’

DMX and XLR look pretty similar. But the way they carry information is different. In a pinch, you can try to use them interchangeably, but I don’t recommend it. When in doubt, look for tiny white writing on the side of the cable what kind it is.

Also, take the time to coil them carefully. In fact, any cable that carries a ‘signal’ even if it’s an extension cord, will last longer, look better, and be easier to store if you loop it gently. Do NOT coil it around your elbow; doing this pulls and twists all the he little mini-cables inside to the cord and it gets all crazy which-a-way more and move over time, degrading the longevity of the cable. Reusable velcro strips, gear ties, or zip ties, are a nice way to keep things organized.

RCA

These cable are used to connect audio and video sources to amplification. Sometimes an RCA cable has three heads. The yellow is usually for video, and the white and red are for audio. These are common for plugging televisions into stereos. Also some forms of DJ turntables use RCA cables. Sometimes called ‘cinch’ cables outside of the USA. (RCA stands for Radio Corporation of America.)

Aux cable aka phone jack aka headphone jack

When we say ‘headphone’ jack we usually mean a 3 conductor TRS headphone jack. These are the common cable used to plug a laptop or cell phone into a speaker.

The plug part comes in varying widths, ranging from 1/4 inch to 1/8 inch. You can purchase adaptors so that you can plug an 1/8 in connector into a 1/4 socket. Colloquially, an ‘aux jack’ refers to a 3.55 mm input of a TRS headphone input. For better quality, turn the sound up on your music playing device first (phone, laptop), then turn up the sound on the speaker. Bluetooth: Convenient because it is cable-less. I would NOT rely on Bluetooth to play all your sound cues during a show. If you do, consider that most bluetooth has a range of 35 ft.

Last On, First Off LOFO

This is a rule of thumb for speakers/amps: That popping sound when you turn a speaker on or off is generally bad for the speaker. Turn your speakers ON Last (after you turn on source of audio aka mixer) and OFF First (before you turn off audio source.)

A sound mixer: An interface that allows a user to physically control various sound equipment going in and out. If you have a live band playing into microphones or with amplifiers, they will probably need a mixer. This makes it possible to adjust how each instrument gets amplified. There’s a huge variety of kinds of mixers and to figure yours out, look for a tutorial on the internet.

Misc.

Cleaning Vinegar: This stuff is pungent but effective. You can use it to disinfect hardwood floors or anything else. Add some baking soda and it’s a fizzy science project. A spray bottle with vinegar is preferable to large puddles and sloshing.

Diegetic: This is a helpful word describing when the source of a theatrical element is visible to the spectator/audience/witness. Me holding a flashlight over my head to make a spotlight for myself is diegetic. Someone off-stage shining a flashlight on me is not because source is not obvious to the audience. A boom box on stage playing tapes or a PA with an ipod the performers control is diegetic. The same sound sources play from off-stage, are not.

I like diegetic everything. I will talk to my audience as the narrator in the middle of my dance. It’s an exciting way to think about theater. It reveals rather than conceals.

Part 5: Dancers aka People

Hot Take:

Dances are always about people.

Often when people see dance, they want to know what it is ‘about.’ However, if you played an instrumental piece of music, they are less likely to ask this question. I think that’s because most humans see another human doing something, and we see a story, we seek meaning. If I’m listening to music, I get to be more in charge of what I envision in my imagination. It’s harder to turn the physical reality of a person in front of me into my own story or abstraction. I think the lived reality of the performer is always, on some level, what the dance is about. I also think a lot of Western concert dance has conditioned us to NOT see this reality. How I make the dance is always what the dance is first and foremost ‘about.’ As my friends at Headlong Dance Theater say “the consciousness of rehearsals shows on stage” (or something like that).

Group Dynamics

At various times in the last decade or so as a choreographer, I have been a tyrant, a charismatic guru, a benevolent dictator, a final arbiter and doormat. All of these models can work when there’s agreement, consent, and consistency. The clearer I am about my power as choreographer and director, the clearer I am about what kind of help I need to make the project happen, and the more clearly I communicate not only with the dancers, but ultimately, with the audience.

One of my biggest mistakes as the director of Effervescent Collective in Baltimore from 2008-2014 was that I thought I could make everybody happy. This meant that some people were really happy and others were really bummed. Or everyone was on a low simmer of annoyed with me. I wanted to run a group with fluid membership, where dancers could come and go as they pleased, working on different projects as it suited them. I wanted to provide a space for anyone to get involved, at any time. I also wanted to make dances that required rigorous group training and deep collaborative responsibility to each other. My two intentions were incompatible inside of the same container. It made me a confused and confusing leader.

The projects that helped me and my friends grow the most as performers and dancers were the ones where I was the most intentional and about the time commitment and we found agreed upon ways to hold each other accountable to these commitments. We were asking a lot of each other in terms of time, energy, and trust. By contrast, the projects that helped grow Effervescent’s voice in the city had looser structures with lots of people coming together for a short period over a simple idea. They didn’t require sustained attention from the participants or the audience.

These two intentions were both valuable, but they lost value when I tried to do them at the same time, within the same project. Yikes!

Confidence & Consent

Learning to say ‘no’ to a collaborator or dancer without damaging their confidence as a performer, to ask them to try something else, to guide them closer to what I’m imagining, has been a critical skill. It helps provide clarity and boundaries, honors people’s time and my own ideas. Personally, I don’t like being in rehearsals when the choreography won’t just come out and say it: “no, not like that, can you try like this?” and I also don’t like when someone puts my ideas down, when they make it personal.

If I don’t know what I’m making, I try to be really clear to my dancers, I think they need to consent to the kind of ride they’re on; “Hey, I have only a vague impulse and I need to explore it freely before I refine it? Are you down for that?” Or, if I know exactly what I want to make, I have a clear vision, “I have a plan for the overall movement and composition of this dance, but I don’t like explaining it in the abstract, and it won’t be obvious for a few rehearsals."

Often I think about how I learned to paint. Sometimes I need to start by mapping out all the shapes on the page, find the overall compositions, sort out the negative space. Sometimes I want to start with shading in dark and light. Then there’s the pleasure of doodling, the gesture of the brush, letting the way the paints feels on the canvas dictate what shapes come out.

I do all of these things in rehearsals, depending on what stage of the process I’m in, and what I want the dance to feel like. Sometimes I have a project that needs dancers who are all passionate about open ended doodling. Sometimes I have a project that needs dancers that are meticulous about shape and size. Sometimes I need both.

Not getting distracted or thrown off by every little emotional shift in my dancers or collaborators took practice. Not getting swept up in every little tangential idea but learning to write it down, and save it for later is a skill. Refine your skills for in-rehearsal decision making and trusting your compositional vision.

If I can help people feel confident in my rehearsals, it helps them make more enthusiastic, risk-taking, zany proposals, and I like that. Some risks they take won’t be a fit for what I’m making, and I think of my teacher David Zambrano who often says: I like it, but not today.

More generally, I am a big believer, as both a choreographer and a teacher, in individual feedback. I think it helps people who otherwise may feel invisible feel seen and appreciated. I’ve learned that when I can quickly tell a dancer what I want, even if it’s different from what they’re doing, they gain confidence in me. And, yes, the quickly is important. I got faster with practice.

Also: I have a theory that if more people were encouraged to dance, in any way, at any stage in life, without worrying about it being ‘good’ or ‘right’ or ‘technical’ we’d have a much larger audience for dance. So, maybe consider if there are any potential dancers in your midst whom you’ve overlooked.

Taking Care / Letting Go

Sometimes when a dancer’s vibe is fucking me up it’s because the dancer isn’t living up to their own expectation of themselves. They’re being a perfectionist when I need them to just let it go.

In my own journey as a dancer, I wanted to be SO much better at SO many things, I would get paralyzed in class or rehearsal, not able to pick a focus. Some choreographers and teachers interpreted this as laziness or resistance. I felt like there some something wrong with me and I didn’t believe it could be fixed. I know now that you can’t help someone who doesn’t want to be helped. But you can hug someone who is hurting, take a three minute break, and affirm everyone’s existence.

I’m always tweaking the balance of trusted collaborators with new faces. I want to bring new people into my way of dancing and I also want to feel relatively comfortable and safe in my own rehearsal process.

Feedback, Dramaturgy

Dramaturgy is a practice that originates in German theater in the 18th century. It’s (more or less) the research-informed editing and presenting of pieces of a performance. For me, it is a helpful approach that overlaps with the approaches to anthropology I learned in school. Both anthropologist and dramaturg seek to study, understand, and illustrate the value structures of something or someone without imposing their own values. What is the logic/ belief system/ culture of this dance? How do all the elements — choreography, lighting, sound, costumes — reflect that system?

I often share dances-in-progress with a well-curated test-audience of supportive friends. When I do this I’m listening for the way the audience responds in the moment. I find this non-verbal information way more helpful than what people have to say after. When does the audience laugh? Smile? Where are they looking? When do I feel their attention waning? Do they hold their breath? Do I care?

As an audience member, my opinion about a dance I’m watching is about me and my desires, not the choreographers. If I am called to help someone else make their own dance, I want to help that dance maker make their dance, not my dance. To this end, an observation is often more useful than an opinion. For example: “The dancers were in lines throughout the piece, except for one moment when they were in a circle” is different from “I liked/disliked the moment when the dancers suddenly made a circle."

But sure, as a choreographer, I sometimes seek the opinion of other choreographers, directors, or designers whose values I share and who will challenge me with a difference in taste, perspective, or skillset. Knowing and clearly asking for what I need in the moment of feedback is on me.

Another expression comes to mind here: ‘Don’t go to the hardware store for milk.’

Multi or Interdisciplinary

Dance is already interdisciplinary. Whoever says it’s not, isn’t paying attention. Even ballet, the historically most normative, status quo, well-funded version of concert dance in the United States, comes from an aristocratic ritual that involves dance, theater, music, visual art, and a hearty helping of appropriated folk dance. I bring this up as encouragement to let your dreams and curiosity guide you beyond, between, and through whatever mediums the adventure requires.

That said, at some point, you got to make decisions about quality and craft. If your show is in three months, maybe there’s not really time to learn all the new skills — sewing costumes from scratch for the projection mapped video during the keytar solo – to do the very complex multi-medium performance idea. It takes time to master a craft, to develop virtuosity. I think of virtuosity as any skill practiced so deeply and thoroughly that the performer is in total control. They can push the edges of their own ability with outcomes somewhat predictable to them, but surprising to the viewer. As Miguel Gutierrez is often pointing out in their work and writing, anything can be virtuosic: pirouettes, head spins, hand stands, burping, walking, percussion, booty bouncing, popping, crying, you name it.

Part 6: Capitalism

How To Pay For It?

In my twenties, when I lived in Baltimore during the economic recession circa 2009 - 2014, I threw a lot of party-fundraisers with sliding scale admission. We’d use the money from entry and ‘beer donations’ to put on the next show. Venues got paid, but we as dancers didn’t. It meant some people couldn’t always work with me. But I couldn’t figure out what else to do. Funding art projects, and the economics of art making is a whole different ‘zine. Andrew Simonet and Artists U have got this covered.

It’s definitely gotten harder as I get older and crave a kind of security. I’m not up for endless warehouse parties anymore. My life costs more. My lived experience, as a very privileged person, is that we’re in a broken system of funding. Or, it’s not broken, it’s built to be bad, to grind us down. Capitalism doesn’t value people or culture, only the capital or commodities people and culture can generate.

Compared to other comparably wealthy countries, the US provides little in social services like child care, parental leave, health insurance, and unemployment. When artists, like everyone else, have their basic needs met, there’s more room for artists to experiment and take risks. There’s also a more robust audience population to go see and pay for art. I’ve only lightly looked into the history of non profit funding in the United States, as well as the history of the National Endowment for the Arts, and its cause for a raised eyebrow (or two.)

I want to have more funds to pay people, including myself. It feels like the best I can do is be transparent about costs, and make sure everyone involved knows what they’re in for before we get started.

That said, if you’re collecting money from an audience, create an easy to use, clear system of tracking revenue (money that comes in), expenses (money that goes out), and profit (what’s left of revenue after all expenses are paid.) Again, asking someone who is good with spreadsheets and accounting to help you can really smooth out the process.

If you collect money in person, a cash box is really helpful, and a printed spreadsheet to notate what’s in that box at the beginning and end of the night. Keep some extra envelopes and pens in there if you need to dive up cash into different categories. Don’t forget the petty cash! This means having small bills on hand to make change. Nowadays, there’s lots of way to collect money via the internet. You can print out QR codes for payment apps.

Document!

In my twenties, I rarely put the resources into filming my dances. I didn’t see a need at the time. We didn’t have cameras on our phones and filming was an expense I generally didn’t bother with. Now, the little video I do have from that time is my art journey is precious. AND ALSO: I’m grateful not all of it was filmed, uploaded, and turned into a digital narrative.

Fortunately, I had photographer friends who snapped beautiful shots along the way. I also have many notebooks and some well-organized little bits of process ephemera. I know many people who have endless video footage they don’t use. Now, as I’m making a dance, I’m also making the memory, or the archive of that dance, and I think about that as I go. My biggest advice would be to download files immediately if they’re sent via a downloadable link. Store important digital things in two place. Back up the back up. Like old clothes, get rid of old files you’re not using.

Reading as relates to this ‘zine:

- Emergent Strategy, adrienne marie brown.

- Making Your Life as an Artist, Artist U (free PDF online, but buy the book if you can)

- The random writings/articles of Miguel Gutierrez (free on their website)

- A Choreographic Mind, by Susan Redhorst (sadly out of print)

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, (free online)

A ‘zine inspired by this ‘zine:

- How to Build a Dance Floor, by Sarah Chein

A ‘zine that influenced the title of this ‘zine:

- How to Not Always be Working, by Marlee Grace

Thanks for spending time with me.

Footnotes

← 1. For example, one of the forms I dance is Vernacular jazz; the adjective ‘vernacular’ distinguishes it from Muscial Theater jazz. Musical Theater or Theatrical jazz is an extension of a branch of jazz family tree, predicated on the Euro-centric, white concepts of ‘technique’ that originates in Ballet as has nothing to do with the origins of jazz as an Afro-American vernacular expression. Until recently, it has served the interests of those with economic resources — running university dance departments, producing heavily funded shows — to perpetuate the idea of Theatrial jazz as the ‘normal’ or even the ‘only’ form of Jazz. This is just one example of many of how the status quo hides in plain sight.

© Copyright Lily Kind 2019, 2021, 2024 — Published with Permission